See as well:

Family Stories:

1. Noah & 1) Minna u. 2) Josefine/Sophine Grünbaum

2. Abraham & Fanni (née Fuchs) Schlesinger

3. Bertha (née Grünbaum) & Jacoby Seckel

Descendants Lists:

1. Hirsch & Golde (née Kohn) Grünbaum

2. Abraham & Veilchen (geb. Lang) Schlesinger

3. Noah & 1) Minna u. 2) Josefine/Sophine Grünbaum

See as well:

The Postcard Collection of Ilse Grünbaum

2019: Stolpersteine for the Frankenberg and Grünbaum Families

*****

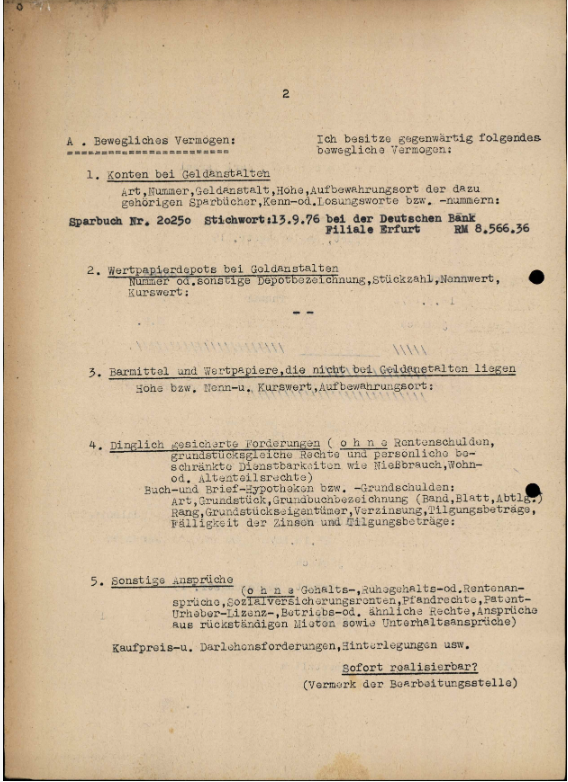

Karl Grünbaum was the youngest son of Noah Grünbaum and the only child of Noah and his second wife, Josefine/Sophine Grünbaum to survive infancy. He was born in 1876 In Themar and lived there until 1913, thirty-seven (37) years in total.

In the first years of his life, Karl Grünbaum lived at Hintertorstraße 170 (today Bahnhofstraße 20) about halfway between the Market Place and the Bahnhof/railway station. He grew up with two half-siblings, the children of Noah and his first wife, Minna (née Friedmann). Hugo had been born in 1868 when Noah and Minna still lived in Walldorf/Werra, while Minna was born on 28 February 1872 in Themar and named after her mother, who died on 8 March 1872 of complications from her daughter’s birth.

In the later 1880s — we believe in 1886 — Noah Grünbaum moved his business and family from Bahnhofstraße 170, as Hintertorstraße was renamed, up the street to #150, closer to the railway station.

*****

Significant changes occurred in Karl’s life as the twentieth century began. First, Noah Grünbaum died on 29 January 1901; according to the 1895 will (to be found in the State Archives of Thüringen in Meiningen), his two sons were to take over the business together. However, if their partnership broke down, Karl was to receive the business as a sole share. (Josephine/Sophine was to receive back the 3500 marks she brought into the marriage.)

Entries in the Regierungsblatt/Goverment Newsletter of the Duchy of Sachsen-Meiningen suggest that Hugo and Karl had already gone their separate ways before their father’s death. An entry on 24 September 1901 informed that Karl Grünbaum had been registered as the sole owner of the N. H. Grünbaum Company. A subsequent entry dated 4 October 1901, indicated that Hugo Grünbaum already had his own business, Hugo Grünbaum of Themar, and that he was adding a Schnittwarengeschäft/dry goods store to this company.

For the first years of the 1900s, Hugo and his wife Klara (née Schloss), who had married in 1898, lived and ran their business in Bernhardtstraße outside the city walls (address unknown). Their first child, a girl, was stillborn in 1901; in 1903, a healthy second daughter, Mira, was born. Karl lived at Bahnhofstraße 150; his mother, Sophine, probably lived with him until her death on 25 November 1903.

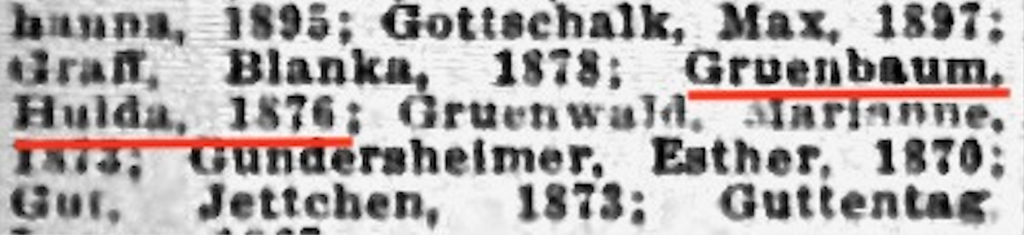

In May 1904, Karl married Hulda Schlesinger. Hulda was the same age as Karl, born in 1876 in the small town of Wasungen, where the Schlesingers were one of a very few Jewish families in the town. Her parents were Abraham and Fanni Schlesinger (née Fuchs), and she had two brothers: Julius, b. 1874, and Gustav, b. 1883. Hulda and Karl were also related through their Schlesinger connection: Sophine Grünbaum, née Schlesinger, was the daughter of Kappel Schlesinger (b. 1809), and Hulda was Kappel’s grand-daughter, and Sophine’s niece.

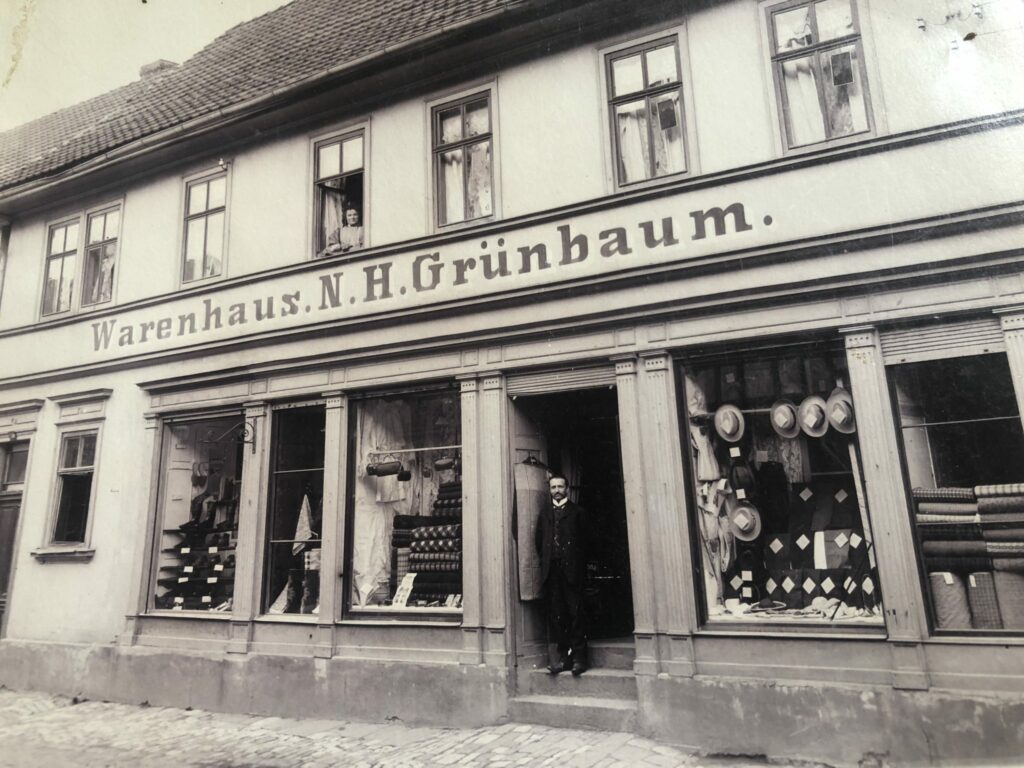

In 1905 Hugo made a significant business decision which doubtless affected Karl and Hulda. Berta Grünbaum, daughter of Noah’s brother Löser, and her husband, Jacoby Seckel, decided to leave Themar. Hugo decided to take over the Seckels’ business, which they had run on the Market Square since the 1890s. On 1 May 1905, Hugo announced the opening of the business in his name and its relocation from the Market Square to Bahnhofstraße 123, more or less right across the street from Warenhaus N. H. Grünbaum. Hugo and his wife, Klara, and their young daughter, Mira, b. 1903, moved from Bernhardtstraße (now Leninstraße). (Daughter Else was born after the move, on 17 July 1905.) Karl and Hulda continued to operate Warenhaus N. H. Grünbaum; in the photo below, one sees Hulda at the upstairs window and Karl in the doorway.

We do not know if Karl and Hulda tried to start a family earlier in their marriage; what we do know is that, on 29 January 1911, nearly seven years after their marriage, Hulda gave birth to a little girl on 29 January 1911. They named her Irene and immediately announced their happy news in the local newspaper. The wording of the announcement suggests that all was well with the infant. However, Irene died five days later on 4 February 1911.

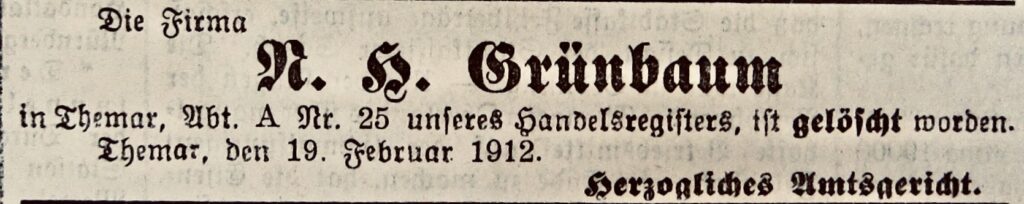

In 1912, Karl sold the business to Markus Rosenberg and deregistered the N. H. Grünbaum company in the Duchy of Sachsen-Meiningen Business Register/Handelsregister. The reasons were probably varied: the advertisements of the two Grünbaum businesses through the years indicate that both stores may have carried similar stock and, while this can often promote a healthy economy, the population base may not have been able to support too many similar businesses. There may have been subtle family pressure on Karl, as the younger son of Noah Grünbaum, to be the one to move rather than Hugo.

It is also possible that Karl and Hulda simply decided to seek their fortune in a larger city. Erfurt, which lay in the State of Saxony, had a population of around 111,000 in 1910 and a Jewish community of around 750 individuals.

Karl and Hulda moved to Erfurt on 1 April 1913 and moved into an apartment in Regierungstraße 19. Their shop was on the ground floor. Almost immediately, Karl took out an ad in the Themar newspaper to let his old customers know where he was.

During the first years of World War I, Karl continued to live and work out of Erfurt. On 29 February 1916, Hulda gave birth to a daughter, Ilse. Then, on 23 October 1916, Karl, 40 years of age, was conscripted into the German army and served until the end.

*****

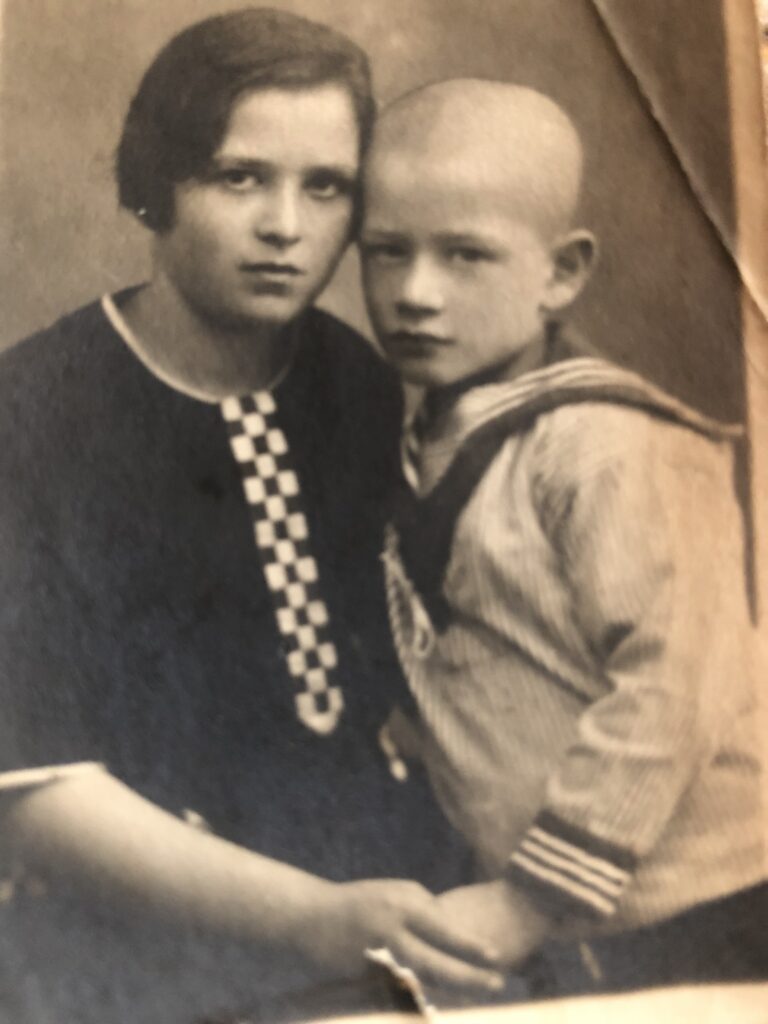

The post-war years began with optimism. On 3 February 1921, Hulda gave birth to a son whom they named Kurt. (Photo shows Ilse and Kurt ca. 1926.) Karl and Hulda established a number of businesses: starting in 1920, they operated Firma Grünbaum & Co., Lack-Farben- u. Kitt-Industrie/Paint, Varnish, and Putty Supplies.

During the 1920s, they expanded their range of offerings. In 1924 they opened a store for Manufakturwaren/general manufactured goods at Regierungstraße 19, and by 1930 they were also selling Webwaren, items such as stockings, socks, etc. Karl was frequently on the road visiting smaller towns and villages in the eastern parts of Saxony and Thüringen. Hulda too travelled as the children grew older.

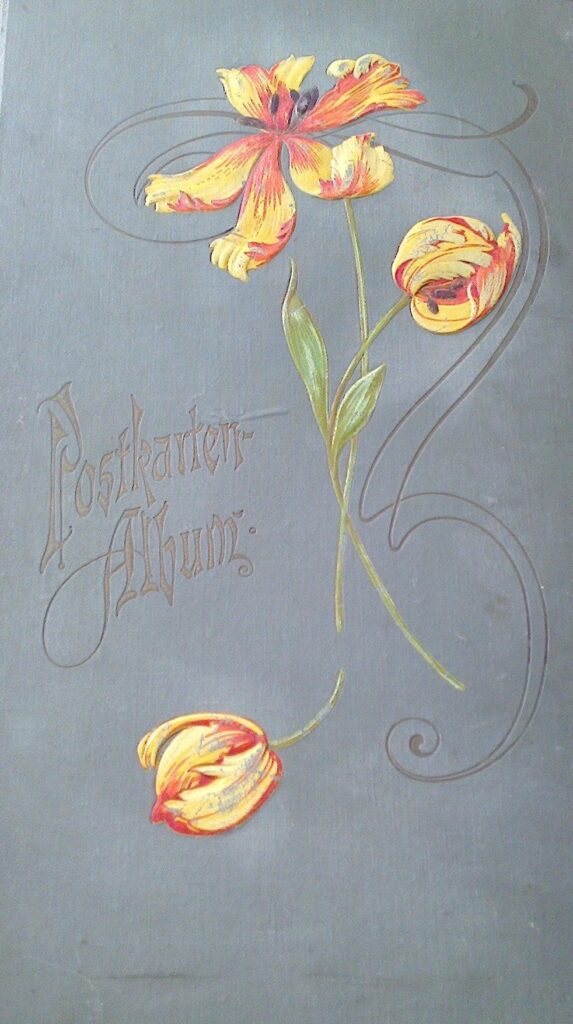

We know something about the comings and goings of the family from the Postkarten Album/postcard collection that Ilse kept from her earliest childhood. It was such a precious possession that it accompanied her to England in 1939 and then on to Australia in 1948. The postcards are a wonderful resource, speaking to us, as they do, of a close and loving family. Karl sent a constant stream of messages from places to which his business took him; both parents wrote to Ilse when she spent her holidays in Schmalkalden with grandfather Abraham Schlesinger and uncle Gustav and his children, Karl and Anni. Grete, Norbert and Max Rosenthal, the children of Minna Rosenthal (née Grünbaum), Karl’s half-sister, also maintained a close connection.

*****

The Nazi Regime’s takeover of power in 1933 opened the door for immediate persecution of families such as the Grünbaums. The government called for war against Jewish businesses, ordering a boycott of all Jewish businesses on 1 April 1933.

By 1936 the number of Jews living in Erfurt had dropped to 440 from 1,290 in 1932 and 831 in June 1933, just 5 months after the Nazi Regime began. Jewish families either left Erfurt and moved to other larger urban centres in Germany or left Germany and even Europe altogether. The family’s socio-economic situation deteriorated steadily during the 1930s and the Grünbaum businesses in Regierungstraße closed in September 1938. In September 1939 Karl was forced to give up his license to travel to market his products.

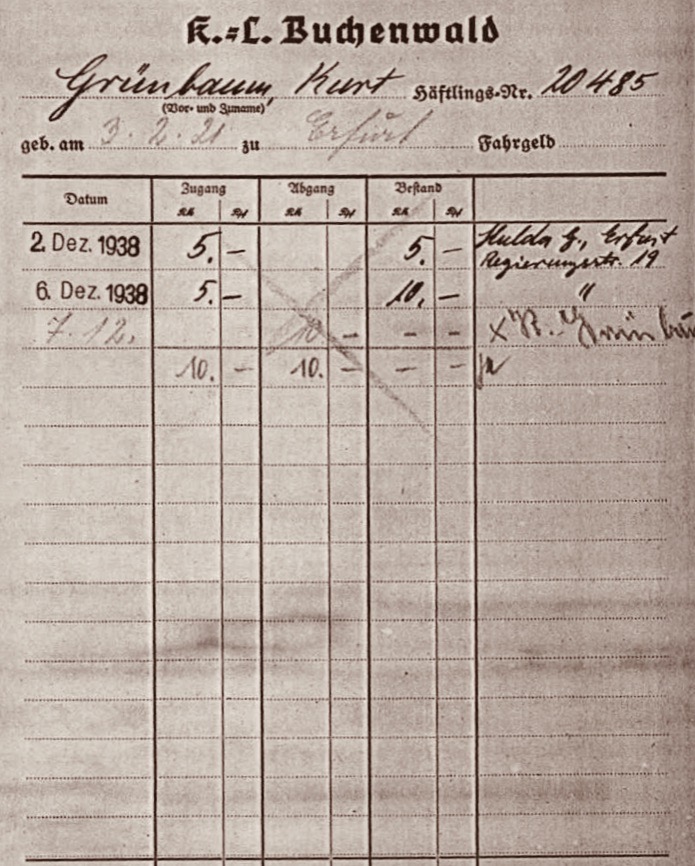

We do not know if Karl and Hulda explored possibilities for emigration before November 1938. But the situation changed dramatically with the 1938 November Pogrom/Kristallnacht. One hundred and ninety-seven (197) Jewish men were rounded up in so-called “protective custody”/Schutzhaft and hauled off to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Karl and Kurt Grünbaum were among them, Kurt at 17 being among the youngest of those arrested. Kurt became Prisoner #20485.

Among the thousands of men crammed into the four purpose-built barracks were their relatives: Hugo Grünbaum from Themar, Norbert and Max Rosenthal from Apolda, and Gustav and Karl Schlesinger from Schmalkalden. Karl would also have known most of the other 17 men arrested and brought from Themar.

Most of the Grünbaum men were released from Buchenwald in December 1938 — Kurt Grünbaum was released on 07 December, his father a day later. The one exception was Max Rosenthal, son of Minna Rosenthal, née Grünbaum, who was kept in Buchenwald until 12 April 1939.

*****

The future was clear: there was no place for Jews in Nazi Germany. Nazi policy, which was to eliminate Jews from Germany through forced emigration or expulsion, remained in place until September 1941.

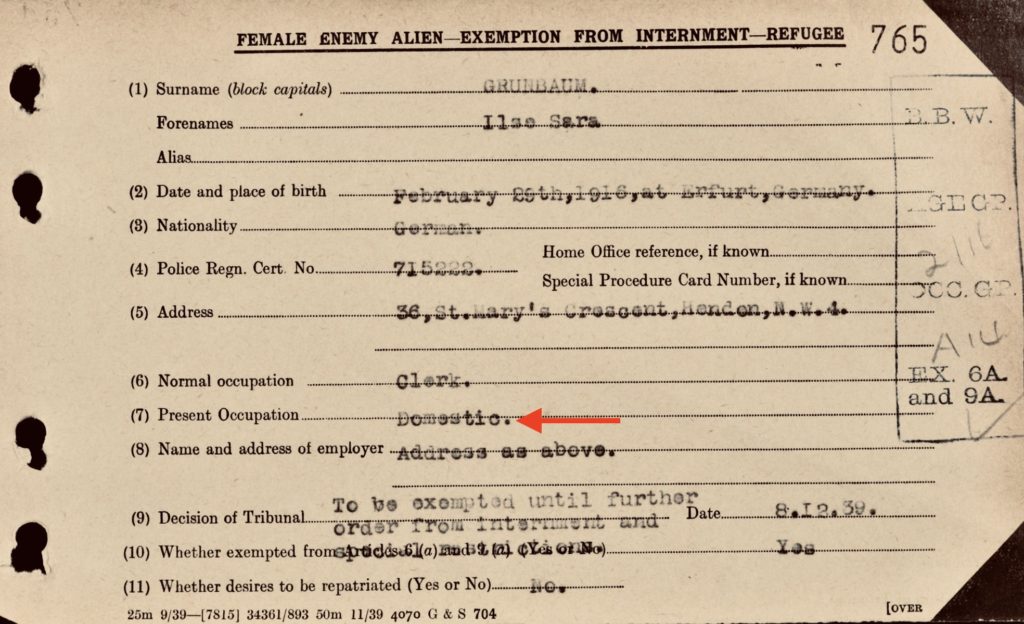

Ilse and Kurt Grünbaum were able to escape before the trap snapped shut, reaching England before World War II began. Ilse left Germany on 04 March 1939, sponsored by the Domestic Permit Program. Kurt followed shortly thereafter. When war was declared in September 1939, both Ilse and Kurt became ‘enemy aliens,’ but, in their first interview with the Enemy Aliens Tribunal, they were declared “exempt from interment.”

The German invasion of Holland, Belgium, and France in May 1940 changed their circumstances. Ilse was allowed to remain in London where she continued to work as a domestic. As her son writes, “to some extent, the war followed her to London. I recall her saying that she spent some nights sheltered/sleeping in underground railway tube tunnels, during the German bombing blitz of London. …[S]he did have a social life, notwithstanding all that, and she maintained correspondence with a couple of friends for many years.”

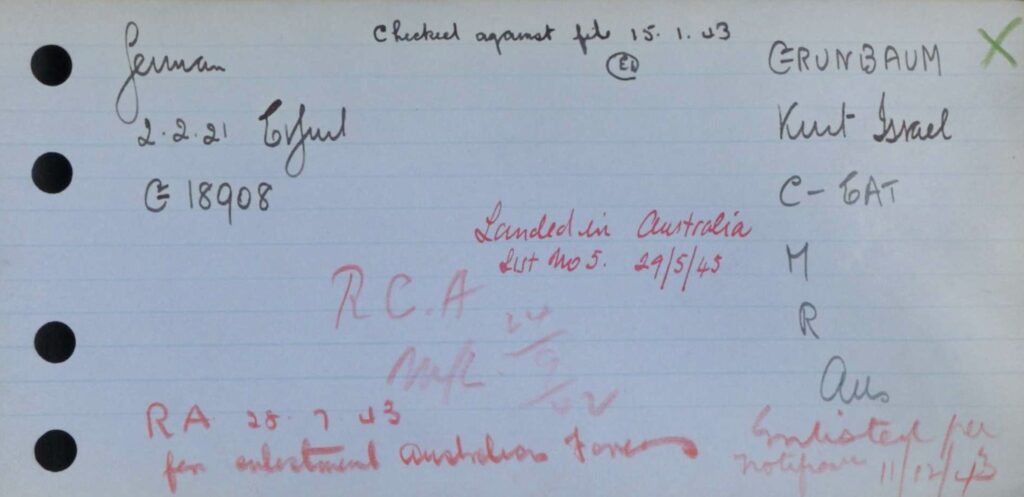

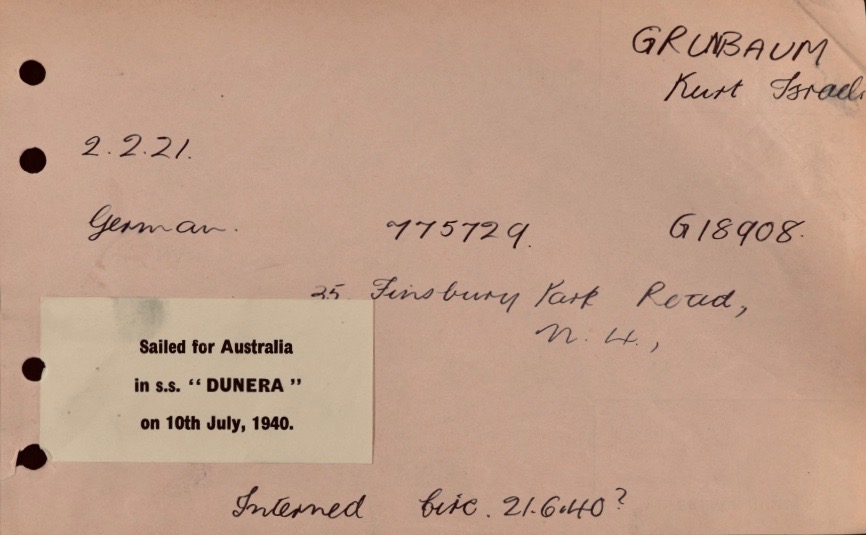

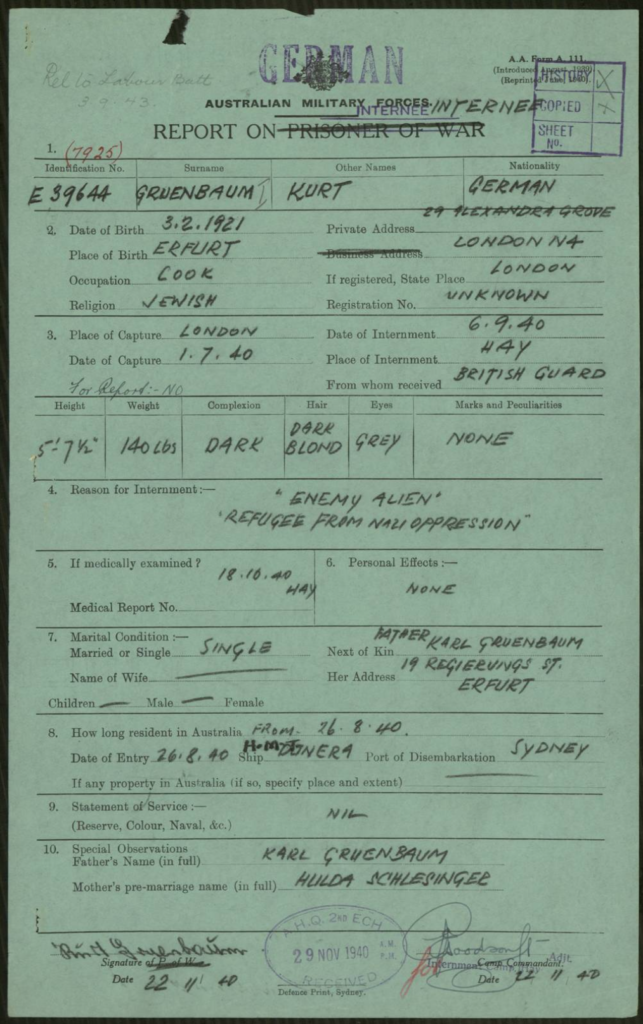

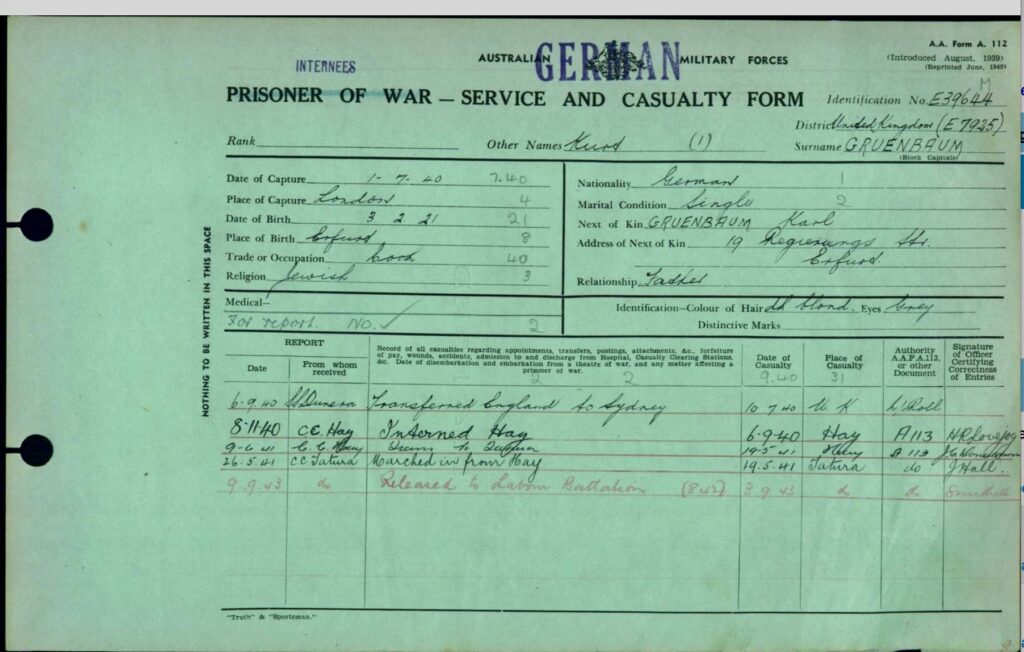

Kurt’s life, however, changed dramatically: The four documents below — which come from the National Archives in Kew, England, and the National Archives in Australia, outline his story. Initially, he lived at (25?) Finsbury Park Road in London N4; on 01 July 1940, he was arrested at 29 Alexandra Grove, London N4. Ten days later, Kurt was deported to Australia on the infamous ship, HMS Dunera. The ship landed on 26 August 1940; on 6 September 1940, Kurt was one of the 1,984 ‘Dunera Boys’ — German Jews and other refugees from Nazi occupied Europe — sent to the internment camp at Hay. They were the first internees of British Government WWII policy. The Australian records identify Kurt’s occupation as “cook”.

*****

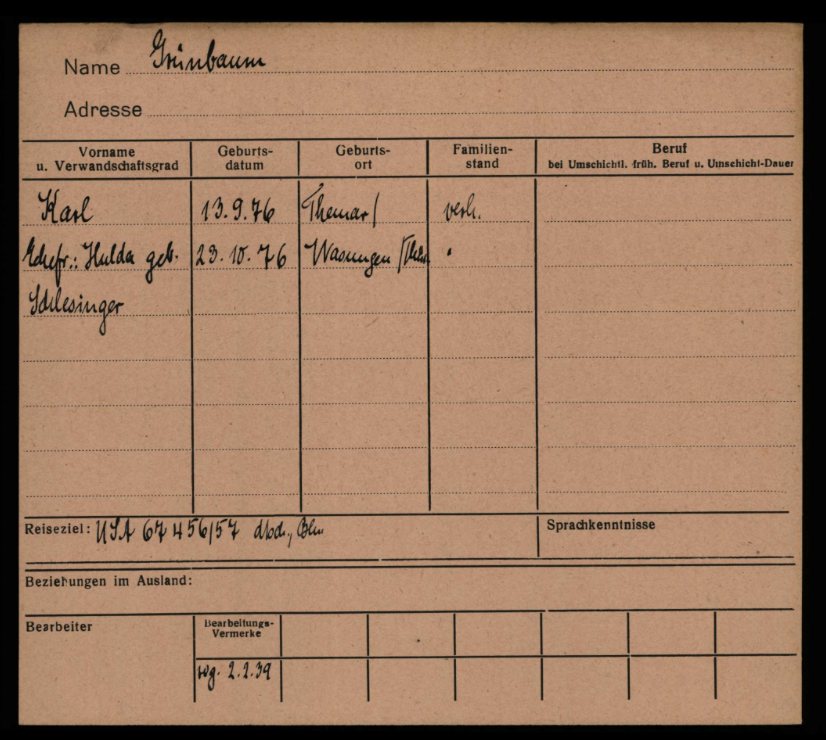

A document in the Arolsen Archives tells us that Karl and Hulda sought emigration to the United States in February 1939. They also tried to enter England,1Jutta Hoschek, Ausgelöschtes Leben, p. 171 and it is also possible that Hulda’s brother, Gustav, who left Germany in April 1939 for Argentina with his wife and two children, did what he could to secure immigration papers for his sister.

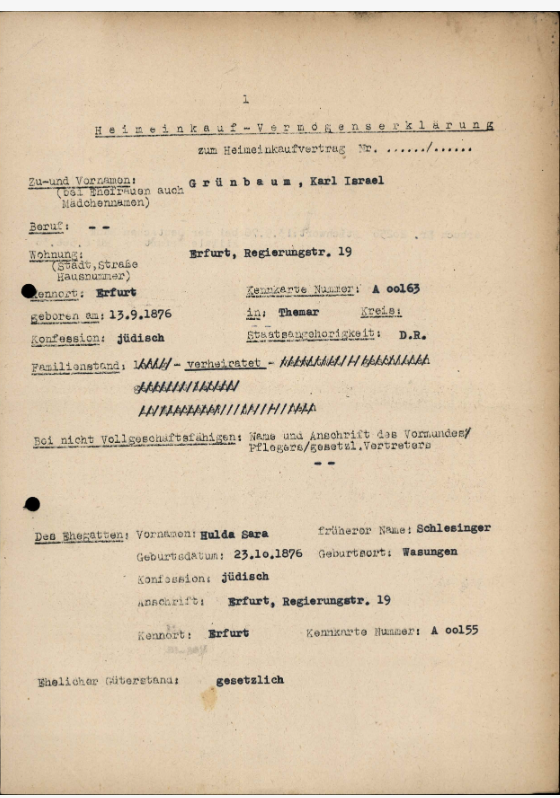

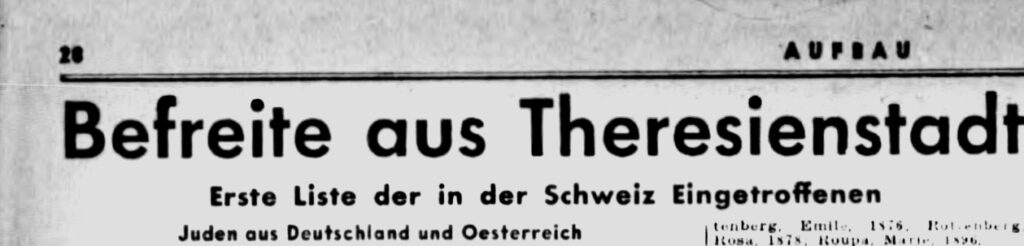

But all efforts failed. In early September 1942, Karl and Hulda learned that they would be leaving Erfurt to live in the so-called “retirement ghetto” in Theresienstadt. They also learned that they would have to use all their remaining assets to purchase a home in the ghetto. We do not yet have images of the two-page Heimeinkaufsvertrag/retirement home purchase contract that they were forced to sign. The Arolsen Archives holds the supplementary document to the contract, the Declaration of Assets,  which tells us that on 13 September 1942, Karl reported that he and Hulda had 8,556.36 RM in the Erfurt branch of Deutsche Bank; this money was to go to the national association of Jews and in turn into Nazi coffers.

which tells us that on 13 September 1942, Karl reported that he and Hulda had 8,556.36 RM in the Erfurt branch of Deutsche Bank; this money was to go to the national association of Jews and in turn into Nazi coffers.

On 19 September 1942, Karl and Hulda were deported from Weimar to Theresienstadt Ghetto; they were on the same train as Karl’s half-brother and half-sister, Hugo Grünbaum & Minna Rosenthal (née Grünbaum), as well as sister-in-law, Klara Grünbaum (née Schloss), and cousin Berta Seckel (née Grunbaum), daughter of Noah’s brother Löser.

The three children of Noah Grünbaum — Hugo, Minna, and Karl — and Hugo’s wife Klara — all perished in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Hugo and Klara died in October and November 1942 (as did Berta Seckel, née Grunbaum); Karl died in March 1943 and Minna died in June 1943.

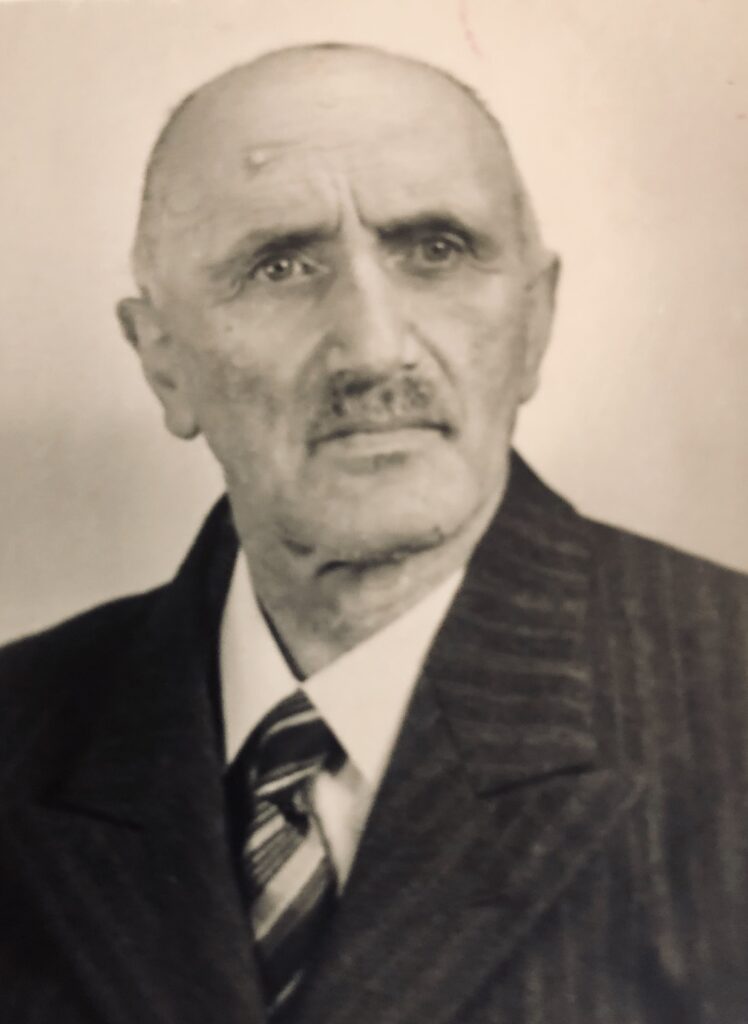

Hulda Grünbaum, however, survived. In early 1945, an agreement was reached whereby Jewish organizations paid Heinrich Himmler for the release of Jews from Theresienstadt Ghetto. On 5 February 1945 at 4 p.m., Hulda was one of 1200 Jews leaving Theresienstadt Ghetto for Switzerland. Around 6 p.m., the train crossed the Swiss border at the town of Kreuzlingen and proceeded on to St. Gallen on 7 February 1945. From there, the survivors were taken in groups to various places throughout Switzerland; Hulda was part of a group who went to Montreux in the southwest corner of Switzerland. The group arrived there on 17 February 1945 and they were housed in the Hotel Belmont. Later in 1945, Hulda moved to Locarno and stayed in the Grand Hotel Brissago.

On 16 February 1945, Aufbau, the Jewish newspaper in New York City, published the first list of names of the Jews who had reached Switzerland. Hulda’s name was among them. It is possible that her relative in California, Paul Wildau, who had himself escaped to the United States in May 1938, may have seen it and followed up as quickly as possible to make contact.

On 11 April 1945, Paul Wildau sent the following telegram to Hulda at the Hotel Belmont:

“ILSE KURT WELL. ILSES ADDRESS FLAT 24 HAVERSTOCK HILL 69 LONDON NW3 PVT KURT GRUENBAUM V513682 8th EMPLOYMENT COMPANY AMF [AUSTRALIAN MILITARY FORCES] AUSTRALIA KISSES = PAUL WILDAU

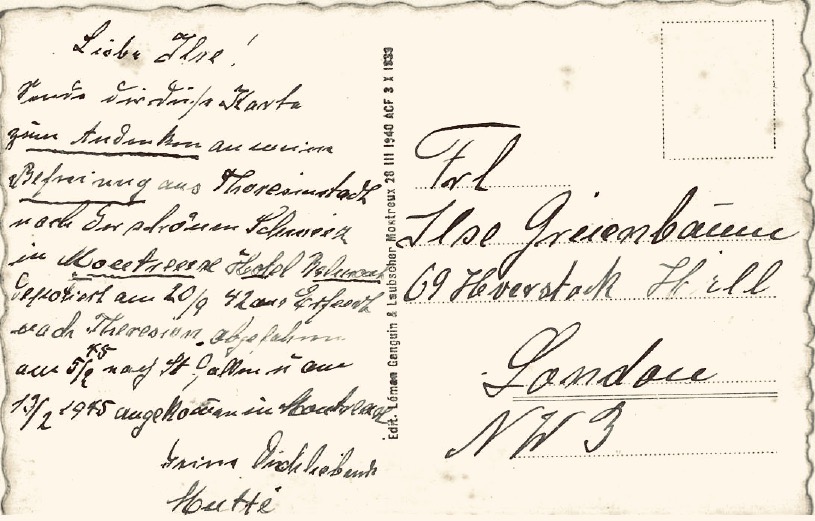

Hulda wrote a postcard from the Hotel Belmont to Ilse shortly thereafter:

Dear Ilse:

“I am sending you this card to remember my liberation from Theresienstadt to beautiful

Switzerland in the Montreux Hotel Belmont. [I was] deported on the 20th September 1942 to Theresienstadt and left for Switzerland on 5 February 1945. Arrived in Montreux on 13 February. My deepest love, Mutti.”

And on 11 November 1945, Hulda wrote to Kurt from the Grand Hotel Brissago, Locarno, where she had been taken to recuperate: “Dear Kurt, I send you the very warmest greetings from beautiful Switzerland. Love, Mutti.”

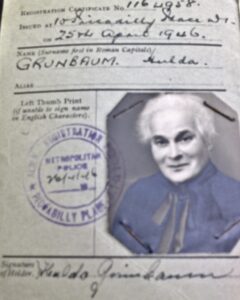

Hulda Grünbaum left Switzerland for England sometime in the winter/spring 1945-6. In the document dated 25 April 1946, she was living at 10 Piccadilly Place, London W1.

She and Ilse remained in London plowing through the endless bureaucracy to acquire the papers that would allow them to travel to Australia to join Kurt.

Ilse acquired her papers in April 1947, Hulda in September 1947. But it was another nine months before they set out on 13 May 1948 for the long trip to Australia: first, by ship for New York, then to San Francisco and finally on 25 May 1948 aboard a Pan American flight to Sydney Australia.

Hulda, Ilse and Kurt (who formally changed his name to Ken Green) remained in the area around Melbourne, Australia for the rest of their lives. Both Ilse and Kurt married and raised families. Wedding Albert Meller & Ilse Grünbaum-Hulda at right of photo

Hulda Grünbaum died in 1963. Ilse Meller, née Grünbaum, died in 1981, and Ken Green died in 1983. Both Ilse and Ken married and formed families in Australia, and it is their children who are sharing with us their family treasures to help tell the story of their grandparents, Karl and Hulda Grünbaum! We thank them.

If you have any information or questions about the Grünbaum or Schlesinger families, which you would like to share, please contact Sharon Meen @ [email protected]. We would be pleased to hear from you.

Sources:

- Jutta Hoschek, Ausgelöschtes Leben. Juden in Erfurt 1933 – 1945. Biographische Dokumentation. Verlag Vopelius; Auflage: 1. Aufl. (9. November 2013), pp. 170-1.

- Aufbau is available online at:1. https://archive.org/details/aufbau

- Arolsen Archives

- National Archives of Australia.

- National Archives, Kew Garden.

- Themar City Archives